ANTIQUES, October, 1926

Toy Banks

By Willard Emerson Keyes

Illustrations from the collection of David Moskowitz

TO whom is the world indebted for the

child’s savings bank? Could it have been Benjamin Franklin, that man of many

inventions, whose maxims designed for encouragement of thrift are among our most familiar

quotations? Or was it some later and humbler genius — an ironfounder, perhaps,

seeking profits from a by-product during a dull season? May it not be that the toy was

naturally suggested by the founding, in 1816, of the first chartered banks for savings, or

by the strife over the United States Bank in Andrew Jackson’s time? It is impossible

to say; for, by their very nature, these little receptacles for vagrom pennies were not

precisely toys, nor were they a child’s necessaries like pattens and copper-toed

boots.

TO whom is the world indebted for the

child’s savings bank? Could it have been Benjamin Franklin, that man of many

inventions, whose maxims designed for encouragement of thrift are among our most familiar

quotations? Or was it some later and humbler genius — an ironfounder, perhaps,

seeking profits from a by-product during a dull season? May it not be that the toy was

naturally suggested by the founding, in 1816, of the first chartered banks for savings, or

by the strife over the United States Bank in Andrew Jackson’s time? It is impossible

to say; for, by their very nature, these little receptacles for vagrom pennies were not

precisely toys, nor were they a child’s necessaries like pattens and copper-toed

boots.

There is no literature of the depositories for children’s savings. Patient search fails to bring to light the story of their origin. Such meager information as we possess indicates that they made their appearance not much, if any, earlier than the middle of the last century. At any rate, none of the banks pictured here bears positive evidence of having existed previous to the Civil War. The oldest obtainable catalogue of toy manufacturers that lists children’s banks bears no date, but, from certain obscure allusions in it to the Peace Jubilee in Boston, we may infer that it was published about 1870.*

*In this catalogue is an illustration of the Chronometer Bank — A Novelty in Toy Banks — and this description: "The coin, put in at the top is deposited in the vault below, and a mechanical device indicates the number deposited. The upper index contains the numbers from 1 to 10; the lower from 10 to 100. This is supposed to be the work of Father Time, represented in the Medallion as endeavoring to turn a cent into a dollar, suggesting that the accumulation of wealth is the result of the proper employment of Time and Money."

It is certain, however, that toy banks, at any rate of

a simple design, were plenty, long before the Peace Jubilee. There are persons now living

who recall, in all their vivid brightness, scattered golden days in that tragic time of

the conflict between the States, when the war-drums still were throbbing; and, distinct in

the picture, standing out clearly in the recollection of the cluttering furniture of the

old sitting room, is a little cast-iron bank. Perhaps this object reposed on the mantel

— the carved, white marble mantel of mid-Victorian years — the mantel which

never knew the glow of a cheerful blaze upon the hearth beneath. Perhaps it rested on the

whatnot in the corner, facing those delirious forms in sable haircloth and tortured black

walnut which seemed to the eyes of their generations to establish a standard of beauty in

household furniture that should endure to be the envy and despair of all posterity to

come; but it was there — childhood’s penny bank.

It is certain, however, that toy banks, at any rate of

a simple design, were plenty, long before the Peace Jubilee. There are persons now living

who recall, in all their vivid brightness, scattered golden days in that tragic time of

the conflict between the States, when the war-drums still were throbbing; and, distinct in

the picture, standing out clearly in the recollection of the cluttering furniture of the

old sitting room, is a little cast-iron bank. Perhaps this object reposed on the mantel

— the carved, white marble mantel of mid-Victorian years — the mantel which

never knew the glow of a cheerful blaze upon the hearth beneath. Perhaps it rested on the

whatnot in the corner, facing those delirious forms in sable haircloth and tortured black

walnut which seemed to the eyes of their generations to establish a standard of beauty in

household furniture that should endure to be the envy and despair of all posterity to

come; but it was there — childhood’s penny bank.

During the long months of the child’s year, the toy bank accumulated its hoard of pennies — gifts and rewards and payments. At Christmas time it disgorged its treasure, but only by a tedious process of shaking and tilting and twisting, until the coins slipped, one by one, out of prison to pursue again their adventurous course through a wilderness of pockets.

Such toy banks of the commoner sort were patterned on the large square mansions which had been built out of fortunes made by privateering in the War of 1812. Each edifice was surmounted by a cupola, and above the blind door, over which ran the inscription Bank or Savings Bank, appeared the slit through which the coins found sanctuary. In the Sunday School libraries of that period, side by side with Harry Castlemon’s enthralling romances of Frank on a Gunboat and Frank on the Prairie, were ranged stories of hardened fathers who crept at midnight into the chamber of an innocent little son or daughter, emptied the cherished toy bank which stood upon the shelf and carried off the contents to propitiate the Demon Rum. The special tragedy of such occurrences lay in the fact that the child had invariably fallen asleep while formulating the high resolve of taking the money from the bank, next morning, to buy physic for a mother on the brink of dissolution from consumption, or halitosis, or other fatal malady.

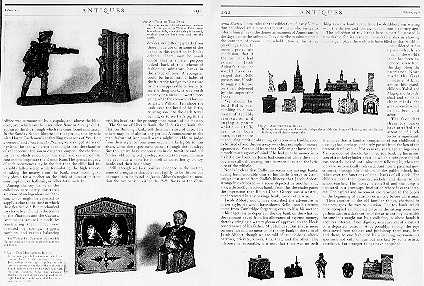

Among the toy banks in the collection here partly illustrated are some of an ingenious mechanism, which might be expected to supply a clue to the time in which they flourished.* But mechanical toys have been found in the tombs of the Pharaohs and the Caesars. Archimedes amused himself by constructing them. They were operated by springs, triggers, tumblers, and various balancing devices, not differing greatly from those made use of in some of the banks in this collection in Philadelphia. There may be small doubt that a sinister purpose lurked back of this scheme of fashioning miniature banks in the shape of toys. A youngster could be lured into a habit of thrift utterly foreign to his nature by his unappeasable curiosity to see the thing work. It was worth a penny or a nickel — worth foregoing what the coin would buy — to watch William Tell shoot the cash over the head of his little, trusting son into the dark tower behind, or to see Pat’s pig flirt it with his hoof into the grinning open mouth of his master.

*The William Tell, Tammany, Pat and His Pig, and other early patent marks of the 1870’s and 1880’s.

The Statue of Liberty Bank, the U. S. Grant Bank, the Flatiron Building Bank, tell their own story of date. The others may be of almost any period. A connoisseur in the manufacture of iron small wares might be able to judge from their style, or from some occult marks legible to him alone, when these specimens passed through the foundry. But though we have connoisseurs in old furniture and old fabrics, old coins, old jewelry, and old tableware, no man has yet made a name for himself ass an authority on toy banks and their beginnings.

Still, though we lack positive evidence in the matter, some of a negative character not lightly to be thrown out of court is to be found in Jacob Abbott’s neglect to mention the toy bank in either the Rollo Books or the Franconia Stories. These tales for the edification of early Victorian childhood are a mine to the antiquary who wishes to inform himself as to the domestic manners of Americans in the days before the railroad. They describe in minute detail the contents of rooms — household utensils, furniture, playthings, and tools. It seems a pretty safe conclusion, that if the toy bank had existed in Jacob Abbott’s time, he would have arranged that Rollo possess one, if only to suggest a lecture on thrift delivered by the impeccable Jonas.

We should behold Rollo, succumbing to a moment of terrible temptation and buying a penny whistle — a trifle dear to a boy’s heart, but of no use in acquiring merit or obtaining salvation — a bauble, soon to be tired of and thrown away — a clear example of money squandered. We should learn that Rollo might have spared himself much agony of mind if he had put the money into his little toy bank, as Jonas had counseled while the small boy was still deliberating, torn between duty and the lyric lure of the whistle.

Nor is it clear that Rollo ran across any savings banks during his memorable visit to his Uncle George in Cambridge — a scene from Rollo’s history that Jacob Abbott strangely overlooked — a scene depicted by another and, alas, a distinctly frivolous hand. From this the reader gains the impression that Rollo’s Uncle George was a wastrel, not interested in any savings bank, toy or otherwise.

Jacob Abbott would have described the adventure in loftier style. He would have shown Rollo upon his return home from Cambridge forgetting even to kiss his mother in his eagerness to deposit in the toy bank on the whatnot the remnant saved from his allowance of expense money, thereby bringing a watery gleam of approval to the bleak countenance of his father, Mr. Holliday. But that is mere surmise; we find no mention of the toy bank in the tales of Jacob Abbott, though we are told of trundle-beds, wheelbarrows, crickets, knives, this, that, and the other. The inference is reasonable, is it not, that there was no such thing as a toy bank at the time Jacob Abbott was writing — in the thirties and forties, not far from a century ago?

The collection of toy banks here in part illustrated is remarkable for its variety; remarkable for its variety; remarkable also in showing how large a place these objects have filled in that world of unconsidered trifles upon which so much of the world’s labor has been expended, even from the day when the patriarch Noah made the first miniature Ark to amuse his grand-children Tubal and Magog and Arpachshad and to fix in their minds the great event in which he had been chief actor.

The fact that these toy banks have attracted the attention of a collector is significant. It implies that a familiar companion of our childhood is passing; has, perhaps, definitely passed from the ken of the present-day juvenile. Not so many years ago an ingenious Yankee doomed the old-fashioned toy bank by his invention of a nickel cylinder affair, in which a coin once slipped was securely locked until nine more followed it, when the lot were automatically released. And now paternal government, through the medium of the public school, has taken over the functions of small banks of all kinds. The children take their pennies, nickels, and dimes to the school-teacher. The money is collected and the lump is deposited in a grownup’s institution where it earns interest. The capitol and increment are returned to the pupils at the beginning of vacation or a little before Christmas.

Thus another of the old familiar things, cherished in memory, goes the way to oblivion. The toy bank, which once occupied an honored place in the sitting room now gathers dust in a dark corner of the attic until by incredible fortune it is sought out by a collector, in whose hands it acquires interest, if not dignity, as a survival of a lost art or a departed custom. And, possibly, among the toys thus saved from ash-can and junk-heap there may, here and there, be one fashioned by a cunning workman — a specimen not only unique but marked by some artistic excellence. Far stranger things have happened.

Photo Captions

Fig. 1 — ALLURING MECHANISM - No child could long hesitate between the enticements of taffy and the joy of seeing Sambo swallow the penny instead. Sambo would get the penny, or a mule would kick it into safekeeping.

Fig. 2 — WILLIAM TELL BANK - This is an accurate bit of cast iron mechanism. A coin placed on William Tell’s crossbow seldom fails, when the spring is released, to shoot over the boy’s head and into the castle.

Fig. 3 — TWO MECHANICAL BANKS - In the first, Judy holds a tray on which the coin is placed. At the pressing of a lever, Judy swings to the right, slipping the coin into an aperture at the rim of the bank, while Punch delivers a blow on his wife’s head with his club. Patented 1884. The Tammany Bank at the right drops a coin placed on the right hand into a slit concealed by the left arm. Patented 1873.

Fig. 4 — ARCHITECTURAL BANKS - Buildings, imaginary and historical; Independence Hall, the Statue of Liberty, and the Flatiron Building are all clearly recognizable.