THE SATURDAY EVENING POST — May 3rd. 1947

THE SORCERER OF FOSTORIA

By MORAN TUDURY

President of one bank, and owner of 600 others, Andrew Emerine acquired fame by collecting the ingenious gadgets our fathers devised to make thrift tempting to their kind.

It was like the scene from Gulliver’s Travels in which Gulliver awakens to find himself surrounded by a race of pocket-sized citizens, all of them moving in high gear. Everywhere I looked there were the strange comings and goings of Lilliputian figures. Ostensibly, this was a directors’ room where financiers met to direct the affairs of a bank in the $9,000,000 class. But the whole place now seemed to be alive with little people.

There was a French acrobat, no more than six inches in height. He performed for five full minutes on a horizontal bar, skinning the cat with ease and grace, A boy of the same size rode his bike around and around the room, taking all turns with an expert counterbalancing of his body. A small comely laundress vigorously scrubbed her weekly wash in a dwarf-sized tin tub. Standing on the directors’ table was a youth who dipped his pipe into a dish of soapy water and blew bubbles. Being ingeniously constructed of a small bellows and rubber tubing, he was able to perform this miracle. Two Lilliputian pool players, armed with cues the size of pencils, were engaged in a lively game. They didn’t call their shots, but they did show an uncanny skill in dropping balls into the pockets. A midget clown was playing Yankee Doodle spiritedly on a xylophone.

General Grant was slightly aloof from the turmoil. He sat upon a handsome walnut box, enjoying his usual cigar. When it was lighted and placed in the holder in his hand he brought it to his lips, inhaled deeply and then exhaled clouds of smoke. And nobody can tell me that none of these things happened either. I was there. I saw it all.

The impresario of these and some 700 other marvels is a bald, pleasant sorcerer who is in his sixties. His name is Andrew Emerine. Like Merlin, the old-time magician of the Arthurian legends, Emerine has more than one job. Most of the time he handles the president’s duties of the First National Bank, of Fostoria, Ohio. He’s pretty good at it too.

In the bank crisis of 1933 his bank was one of the few in Ohio where depositors could draw out any amount of funds they wanted, without restrictions. When Emerine moves among the folk of his vast mechanical world, his magic wand is a key with which he winds up the clockworks of one of America’s most interesting mechanical-toy collections, the handiwork of mechanicians of rare ability. Many of them won prizes at the great toy fairs that were held at Leipzig before the war. Some were famed Swiss watchmakers. Others were lonely peasant geniuses of the Black Forest, putting together miracles out of the humblest materials — a few pieces of whittled wood and a length of string. They made such articles in the wintertime when most of the farm work was over.

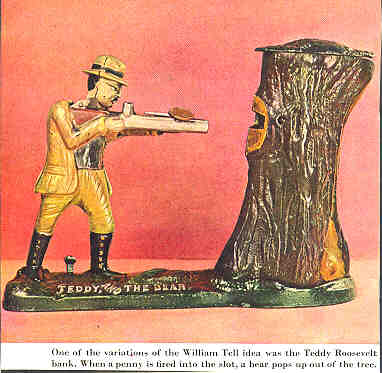

Like the famous toyshop of Geppetto, in Pinocchio, Emerine’s collection includes something of almost everything. There are lovely walking dolls in silks and brocades, graceful dancers and daredevil horsemen. An autoist blows his horn loudly, an organ grinder turns a crank which sets off a music box. There are bell ringers, minstrels, trick animals, drummers, swimming sea lions and waddling ducks. Gen. Benjamin Butler, in full uniform, strides commandingly around the room. Teddy Roosevelt shoots a penny which causes a bear to pop up out of a tree. A mechanical eagle feeds its young. A carrousel goes around and around while music plays.

"Here’s one I want you to see," Emerine said, picking up a gilded bird cage. "It’s a little out of the ordinary." He wound the works that were concealed in the base, and pushed a lever. Turning its head from side to side, the bird flicked its tail, chirping and trilling while the beak opened and shut in perfect synchronization. "It was made in Paris about ninety years ago. The mechanic who made such articles was a high-priced man, earning about twenty thousand francs a year. The song is produced by a small jagged cam in the base of the cage. Many of these birds sang several songs. All you had to do was change the cam."

We passed on to a Negro deacon who had been found by Emerine in an out-of-the-way place in Maryland. When wound up, this preacher gestured vigorously, leaning over and pounding his pulpit with one hand, while the other hand raised and lowered the Book. His head turned from side to side, missing none of the sinners present.

"What makes moving toys attractive is their charm. They’re like old fashioned visitors from the past. Then, too, their mechanical precision is clever. An uncoiling spring, turning a shaft, furnishes the usual motive power. On the shaft are various irregularly cut cams. Each cam depresses a pedal which pulls a wire, which is attached to one of the toy’s limbs. It’s the synchronization of all the movements that produces the lifelike effect."

There are seven huge cases of toys on the bank’s mezzanine floor, where the collection is always on display for visitors.

From one of these cases, Emerine produced a painting. It portrayed two Dixieland banjo players and a dancer. Covered by a glass frame, it appeared to be a perfectly ordinary picture. He turned it upside down for a minute and then reversed it, setting it on the table. There was a surprising transformation. The banjoists began to strum their instruments, and the dancer joyfully cakewalked.

"It’s a sand toy, and they’re pretty hard to find," Emerine explained. "There is a paddlewheel behind this picture. It’s churned by the fall of sand through a small chute. The wheel strikes certain projecting parts of the figures as it moves. That makes the action."

He held up a cast-iron cap pistol. THE CHINESE MUST GO was the legend on its butt.

"This was popular in the days when California was wrought up over the immigration problem. Pistols like this were made in the 1880’s, and sold for fifty cents. A rare one will bring fifty dollars now." He pulled the trigger. A Native Son, which was the hammer, promptly kicked a Chinese in the seat of his pants. A cap in the Chinese’s mouth went off with a bang.

"If it moves, then I like it," Emerine said with a fond smile.

"You can understand why these figures are so lifelike," Emerine said. "Artists paint still pictures and sculptors make motionless figures. But the maker of automatons worked from real, moving life. He had his model go through the desired actions and studied them. Then he broke the whole thing down to four or five elementary movements and set about reproducing them mechanically. Most automatons were made in France. The price depended on the number of movements. A large figure with four or five brought a hundred dollars around the turn of the century.

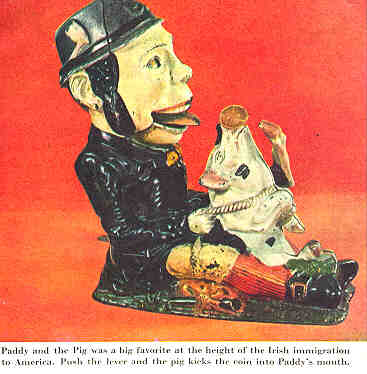

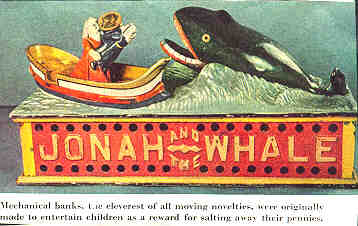

If it moves, then Andrew Emerine probably has it in one of those seven cases. For his collection is not limited simply to key-winder toys. Four of the cases contain more than 600 mechanical penny banks — articles which are pretty hard to find these days. It’s the banks that bring the pilgrim miniature-bank collectors from distant parts to Fostoria. They’ve made Emerine internationally known in the collectors’ world. When their ingenious construction is studied, you realize that these are the cleverest of all moving novelties.

"The idea of the banks was to teach thrift to young folks," Emerine said. "As a reward for salting away a penny, they were entertained by a trick." He removed armloads of metal bands from the cases and then began to dig in his pocket for pennies. "Walter Chrysler used to collect mechanical banks, and he had the right idea. He always kept a can full of pennies on hand. He never was caught short when he put on a demonstration."

He placed a penny in the outstretched hand of a small cast-iron man who sat in a chair. The added weight of the penny moved the man’s arm sharply downward, the penny dropped into a breast pocket and the figure curtly nodded its thanks. Another penny was placed on the crossbow of William Tell. When Tell’s foot was pressed, the penny sped from the bow, knocked an iron apple off his son’s head and neatly disappeared through the window of a small iron tower. Next, a penny was placed on the table of a magician bank. A lever was touched and the magician advanced to the table, covering the penny with a plug hat. When he lifted the hat, presto, the penny was gone.

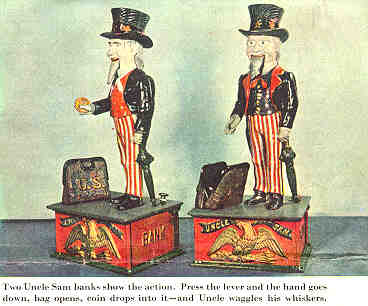

A bank in the Emerine collection that has something of a sinister turn to it is the Uncle Sam model. Harassed income-tax payers find something vaguely morbid about this one. A penny is placed in Uncle’s hand, his hand drops to a carpetbag, which instantly opens, swallowing the penny, and then shuts forevermore. Uncle Sam waggles his chin whiskers in a sardonic manner.

One of the most beguiling of these tricky penny snatchers is one that’s called the Darktown Baseball Battery. It gives you a run for your money. You place a penny in the pitcher’s hand and touch a lever. Then the pitcher throws for the plate, a waiting batter swings and misses, and the catcher blandly pockets your penny.

"These banks sold for a song in the old days," Emerine says with a sigh, "but these aren’t the old days now."

They aren’t. According to him, collectors will feverishly outbid each other for such articles, sparing neither cash nor guile in their efforts to secure a good one in working condition. It would take quite a stack of coppers to equal the value of a rare bank today. Kids of the past might have shown a greater profit if they had thrown away their pennies altogether and simply saved the banks. The milking-cow bank — the product of a foundry of the 1880’s — originally sold for two dollars. Today a collector will gladly fork up fifty times that amount. A dentist bank, once for sale at the same price, now brings a hundred and fifty. The freedman’s bank is the one that Emerine considers among the rarest. It was made by Jerome Secor, of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and sold at wholesale for four dollars and a half. A serious collector places its true worth at $300. One of the reasons for high prices is that many of the collectors are bankers, and they naturally have a sentimental interest.

Many of Emerine’s banks are more modest varieties of the elaborate mechanical gems of the past, those single items that were turned out, for a huge price, for such collectors as the emperor of China. To give you some idea of these ancient masterpieces, one was a mechanical orchestra which played an overture. Another was a flute player, made by a Frenchman, that played musical scores specially composed for it. Some were finger rings which contained moving figures. A watch in the possession of a Swiss collector had a tiny harpist that played a tune.

Few people who view Emerine’s collection probably have any idea at all of the ancient origins of mechanical toys. Yet many of the mechanical principles they admire actually were in use 2000 years ago. The earliest moving figures were of the religious variety — saints with moving lips and eyes. Then came the clock jacks of Europe’s old cathedrals, the sturdy men of iron whose hammers faithfully rang out the passing hours. Strassburg and Nuremberg had some of the best of these. Kings supplied the next encouragement for this pixie industry, hiring expert mechanicians to make elaborate toys with which they hoped to entertain their friends.

Pierre Jacquet-Droz, a Swiss watchmaker of the eighteenth century, was an inventor of superior automatons. His reproductions even wrote poetry and drew pictures of cherubs. These figures are now in a museum at Neuchatel, after passing from owner to owner for 200 years. One such automation, a child made by a French inventor named Maillardet, is in the Franklin Institute, at Philadelphia. For thirty-five cents you can secure seven different specimens of its writing and artistic skill. The history of the robots is rich in legend. Roger Bacon, a wizard of the Middle Ages, is reported to have made a mechanical head that not only talked but also uttered a prophecy now and then when in the mood. Marie Antoinette was once insulted by an automaton. It drew and handed to her a libelous picture.

One of the prize stories is that of the Iron Fly of Charles V. It must have been made by a man who had a certain handiness with tools. This fly dutifully perched on the city’s gates and patiently waited to devour any fly which might dare to annoy the citizens.

An eighteenth-century mechanic fared badly with his products in this line. He took his collection of automatons into Spain, where he exhibited then at a nice profit. So confident was he of their lifelike performance that he advertised them as actually possessed of supernatural powers. Unhappily, this showmanship proved his undoing. He was arrested by the Inquisition for being a necromancer and barely escaped with his life. When he fled, he left his clockwork men to their fate.

The first actual key-winder toys, of the type seen in Emerine’s collection, were made for a child of Louis XIV. They were performing toy soldiers, fashioned of silver by German toy-makers. But it took a British sailor with a mechanical turn of mind to simplify this brand of toy so that it might be produced cheaply enough for general sale. From 1850 to the turn of the century. Nuremberg toy-makers supplied the world’s children with ingenious playthings. It was 1900 before American manufacturers began to offer any kind of competition. One of the earliest American toys to sell in large numbers was a climbing monkey on a string. This was in 1903. It sold for a quarter, and today very likely would bring six or seven dollars if bought by a collector.

Emerine’s own mechanical-toy collecting began only a few years ago. But his interest in the banks has been going strong for more than twenty years.

"It sort of sneaked up on me," he said with a smile. "I used to go into antique shops with my wife, looking for furniture for our home. Every now and then I’d run across a mechanical bank and buy it. The way it worked sort of tickled me. First thing I knew, I had a number on hand. Then I really was hooked. Now I even have descriptive and illustrated pamphlets printed to send out to the dealers. I’ve sent out thousands of these, simply to remind people I’m still looking for a rare item if it comes their way."

Dealers send him mechanical dogs which will nip a penny from your fingers, children who skip ropes for the price of a penny, football games that cost only a penny for a close-up seat. On his shelves are jugglers, penny-swallowing whales, performing eagles and frogs and lions.

"One of the best pieces of luck I had was right in the beginning," Emerine said. "Mrs. Emerine remembered that years before she had seen an old bank in her attic. It was at the family home in Clyde, Ohio. We found it too. It was a circus bank, and today its value is a hundred and fifty dollars. But that was one of the good breaks. I’ve had bad ones. Once a fellow in Kentucky wrote, saying he knew where a rare bank could be bought for fifty dollars. He couldn’t get his hands on it unless he had the money — so he said. I sent him fifty dollars. I never saw the bank or my money again, either. Another time I sent thirty-five dollars to a woman who claimed she had a donkey bank. I wanted one like that. It turned out to be a tricked-up cigar lighter, without any value at all. I kept it. It helps me remember to watch my step."

Another time a piece of Sherlock Holmes work was well rewarded.

"One day I was mooning around, trying to remember if I had ever seen any mechanical banks when I was a boy. Then I thought of something. In the old days I had known a boy who had known still another boy who had a bank. That was the way I remembered it, anyway. It looked like a pretty cold trail. I ran down the bank in Morenci, Michigan. It took a day’s searching. And it was in the hands of still another party.

"Then collectors’ duels are happening all the time. I beat one colleague to a rare freedman’s bank in Mexaco City. But he beat me to another one. It’s a bank I’m still looking for after twenty years. Sometimes I dream about that bank."

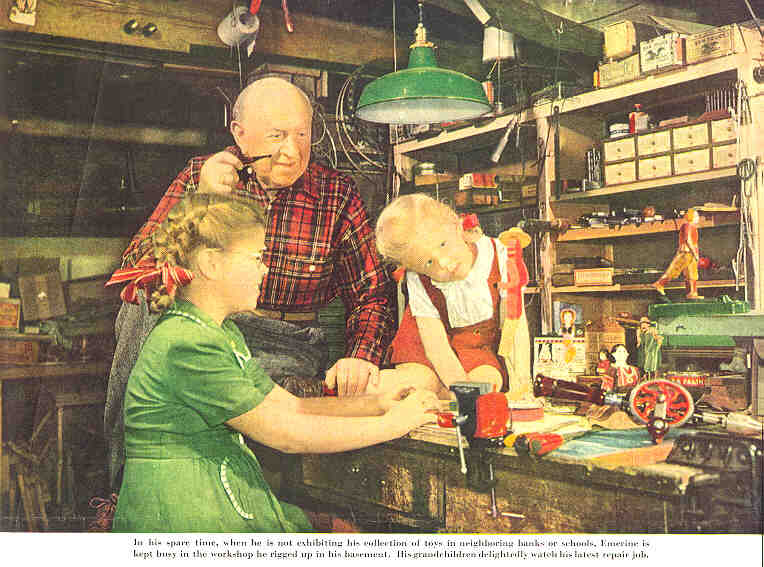

Emerine has become a master repairman of broken robots. In his basement are a press for drilling holes in iron, a lathe for turning parts of banks in brass, a cut-off saw, a band saw, a sander, a planer, a jigsaw and other woodworking tools. He has, on occasion, welded broken parts. Furthermore, when he isn’t using his spare time in this way, he’s making his own plumbing and electrical repairs, or producing furniture in cherry wood with handsomely turned legs, or exhibiting his collection of toys in neighboring banks or schools, or fishing and hunting — just about everything that a busy man in his sixties, with a real zest for life, gets the urge to do.

"There are a number of reasons for the present boom in old-toy prices," Emerine explained. "America discovered its old furniture a few years ago. You know what such things sell for now. Now we’re searching for the playthings of the past. Today, antique and hobby magazines carry ads from collectors who are hungry for old-fashioned toys and banks. The war had a lot to do with increasing this demand. No metal or truly mechanical toys were made then. Scrap drives pretty well cleaned out any that might have been stored in attics. These things formerly could be picked up for nothing. Now any kind of prewar toy will show an increase over its original value.

"The foolish collector appears never to be satisfied and always longs for a few additional specimens. I always tell people this: If they own a cherished old bank with any sentimental interest, then hold onto it and turn a deaf ear to collectors. Of course, it’s the anxious collector who sends prices up. All the old time banks have only relative values. The extremely rare ones actually are worth about half of what the collector is willing to pay. The common and middle-class varieties aren’t worth anything like what the seller imagines."

Emerine, who can go on and on in this vein, continued., "John Hall, a New Englander, was the inventor of the first mechanical bank. It was in 1869. Then came the J. and E. Stevens Company, of Cromwell, Connecticut; the Shepard Hardware Company, of Buffalo, New York; and the Kenton Hardware Company, of Kenton, Ohio. This last firm still does business and has a museum containing its old-time products. Before the appearance of mechanical banks, youngsters owned only what we call ‘still’ or ‘dumb’ banks. The minting of the first United States large copper-cent pieces in 1793 started the production of these banks on a large scale. Before that time, banks were strictly a homemade affair — whittled wood or a shell or gourd with a slit in the top."

It was time to go, but there I was, still sitting.

Emerine at the moment was pulling small objects out of his desk drawer. He wound one of them — a clown who nonchalantly balanced a block of wood on his nose. Then a Toonerville Trolley went into motion. When it reached the edge of the table, the Skipper stopped it himself.

"It’s almost time for you to catch your train," Emerine said, "but wait a minute. I haven’t shown you my collection of mechanical cigar cutters and lighters."

There was a whole case filled with them. He brought out one — a cast-iron Indian who obligingly raised his right foot and kicked forth a match, duly lighted.

He returned the Indian to the case and reached out once more. "Now, here is something. I couldn’t let you get away without seeing this one. When you press this button ——" THE END