House & Garden — July, 1930

"A Penny Saved..." Quaint Curios

Of 19th Century Childhood

Walter A. Dyer

WHEN I was a very little chap,

nearly half a century ago, my older sister owned a toy bank which was one of the things I

quite definitely recall. It was in the form of a little house, of cast iron I believe, and

painted in colors. When you opened the door a little iron man appeared bearing a tray in

his hand. You placed a cent on the tray (if you had one) and closed the door, and the

little man stepped back and dropped the penny into a slot inside the house. I suppose

there was some device for getting the pennies out eventually, but I don’t remember

about that. They were my sister’s pennies, anyway. The contrivance seemed very

marvelous to me, mysterious and virtually inexplicable.

WHEN I was a very little chap,

nearly half a century ago, my older sister owned a toy bank which was one of the things I

quite definitely recall. It was in the form of a little house, of cast iron I believe, and

painted in colors. When you opened the door a little iron man appeared bearing a tray in

his hand. You placed a cent on the tray (if you had one) and closed the door, and the

little man stepped back and dropped the penny into a slot inside the house. I suppose

there was some device for getting the pennies out eventually, but I don’t remember

about that. They were my sister’s pennies, anyway. The contrivance seemed very

marvelous to me, mysterious and virtually inexplicable.

A few years later I became the proud possessor of a mechanical bank of my own. It was of colored cast iron and the front was ornamented with a representation of organ pipes. On top sat a monkey in human clothing. One hand held his cap, the other an outstretched tray. On each side of him was a smaller figure, possibly a begging dog. On one side of the bank was a hand-organ crank. You placed a penny on the monkey’s tray and turned the crank. Bells, somewhere inside, tinkled a sort of tune, the smaller figures turned as though waltzing, and the monkey, whose arms were jointed at the shoulders, simultaneously lifted at the shoulders, simultaneously lifted his cap and dropped the penny into a slot at his feet.

In the bottom of this bank there was a square opening, closed by a piece of iron that was fastened with a lock. On rare occasions, when something like a hundred pennies had been accumulated inside, you took the little key and, with excitement and ceremony, unlocked the bank and removed the stored wealth. This was taken down town by father and deposited in the big bank where it was understood to grow mysteriously so that you might go to college when you grew up.

I owned another bank at one time, but it was a weak vessel compared with these. It was of ordinary brick-colored earthenware, in the shape of a miniature molasses jug. It was hollow, of course, and the only opening was the slot through which the coins could be dropped. I believe the idea was to fill it then break it, and it seems to me that this ceremony was performed on a grand scale in public once in connection with some money-raising campaign for the Sunday School — using other people’s banks! I believe I never got as far as that with mine, however, for I discovered that, in times of financial stringency, the pennies could, with patience, be shaken out onto the bed.

I have never been able to learn much about the origin of the toy savings bank, or how old the idea is. Very likely something of the sort has been discovered in the excavation at Pompeii. I know that Scotch children had such banks a hundred and fifty years ago. They would. A number of English and Scotch potters who specialized in other things than tableware made toy banks in the form of human heads, pigs and the like, hollow and with slots in the top. Toy banks were also made of flint-enamel ware by the United States Pottery at Bennington between 1849 and 1858. They were chiefly in the form of grotesque heads.

Vastly more interesting than the pottery bank, however, is the mechanical

bank, usually of cast iron. There is something about it that suggests German origin, but

all that I have ever seen were apparently made in this country. They are not so

excessively ancient, and yet they date back to the Victorian period which we are beginning

to think of as pretty long ago. I am inclined to think that simple cast-iron banks, some

of them shaped like houses or savings banks, made their appearance about the time of the

Civil War. Possibly some are older than that. More or less intricate mechanical banks were

popular in the ’70’s and ’80s. The earliest printed reference to one that I

have heard of is in an old catalog issued about 1870, and there are patents that go back

to 1873.

Vastly more interesting than the pottery bank, however, is the mechanical

bank, usually of cast iron. There is something about it that suggests German origin, but

all that I have ever seen were apparently made in this country. They are not so

excessively ancient, and yet they date back to the Victorian period which we are beginning

to think of as pretty long ago. I am inclined to think that simple cast-iron banks, some

of them shaped like houses or savings banks, made their appearance about the time of the

Civil War. Possibly some are older than that. More or less intricate mechanical banks were

popular in the ’70’s and ’80s. The earliest printed reference to one that I

have heard of is in an old catalog issued about 1870, and there are patents that go back

to 1873.

The following description is an excerpt from a catalog of the Milton Bradley Company, toy makers of Springfield, Mass., the city of my boyhood. It is dated 1886

THE BIJOU SAFE BANK

A bank and jewel case, 10 in. x 8 in. x 6 in., made of wood and covered with chromo papers in exact imitation of a fireproof safe, as shown by accompanying cut. An opening in the top admits the nickels and pennies to an inner safe only reached by opening two doors, each provided with an ingenious puzzle in imitation of a combination lock. Beneath the inner safe is a drawer for trinkets and jewelry, the front of which is ornamented with a print representing the backs of account books, etc. This toy is an ingenious puzzle and a useful and ornamental piece of bric-a-brac, as well as a novel and attractive bank.

I don’t know what the price was, but I’ll wager that you got a good deal for your money in that bank.

That reminds me of one now in my possession. Where it came from or who the original owner was are mysteries to me. It simply turned up one day in the attic. It is of cast iron coated with silver paint and is in the form of a combination safe. There are two slots, on opposite sides, marked "Dimes" and "Nickels," and some sort of mechanism for unlocking the thing that I have never been able to fathom. Perhaps it is out of order. I have dropped in several dimes and nickels in the hope that they might release some spring or something, but without result. (I often feel the same way about the nickels I send after one another in a telephone pay station.) Some day I mean to take a few hours off and puzzle the thing out — and get my money back.

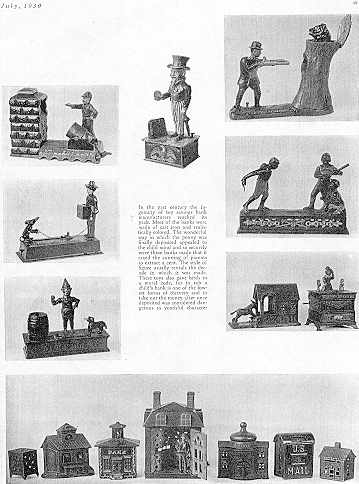

I suppose it would be absurd to call these mechanical banks antiques, though they do belong to a previous century. They are fascinating, though, and I know of two or three persons who have made collections of them. Some day they will be antique, and meanwhile they serve as documentary evidence of the thrift, as well as the artistic standards, of an earlier generation. The banks shown in the accompanying illustrations are from the collection of Mrs. May Bliss Dickinson Kimball of Boston and Amherst, Mass.

They are as quaint, as varied and as humorous as Rogers groups or the older cottage ornaments and figurines, and their mechanical ingenuity adds a further charm. They belong to the period of the Currier and Ives print. Their designs are numerous enough to satisfy the collector’s demands. They range all the way from the simplest to the most complicated.

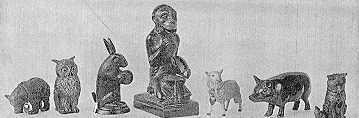

In addition to the pottery banks of various shapes, there are also cast-iron animals with slots in their backs. Some of these animals have removable heads which are fastened on by means of miniature padlocks, the keys to which may be hidden if there is any danger that father, when the stock market goes wrong, may be tempted to rob the baby’s bank. There are also simple banks in the shape of houses, etc., whose only mechanical ingenuity lies in the skill with which the door of exit is concealed.

Most of the mechanical banks include some variation of the device by which the coin is dropped or shot into the slot by a moving figure when a lever is pressed. Thus the colored lady is made to swallow the penny, or the donkey kicks it into the stable, or Uncle Sam drops it into his carpet bag, or the Union artilleryman shoots it through a stone wall with his mortar, or the mother eagle crams it down the throat of her fledgling.

Pat, the hod carrier, dumps the coin out of his hod into an aperture in front of the brick-layer. The trick dog is made to leap up and deposit the penny in the clown’s barrel, or the trained monkey into the Italian’s hand organ. The Tammany bank shows a politician with tainted money in his hand which he slips into a secret place after he has gloated over it. The Darktown pitcher hurls a nickel over the plate, the batter swings wildly, the catcher ducks and the coin disappears between his knees. Their costumes are those of the ball players of the ’80s. And finally young Teddy Roosevelt (you can figure out the date of this one for yourself) shoots a grizzly bear with a penny right through the trunk of a hollow tree, his prowess being proved by the fact that the bear’s head promptly disappears.

These are some of the wonderful feats that the mechanical banks perform. Whether their ingenuity led to greater thrift on the part of their owners I cannot say, but they certainly added something of wonder and amusement to the lives of the little folk of the 19th Century.

(Captions accompanying photos)

Now that thrift has become fashionable it is interesting to look back on the days when we and our parents before us took care of the pennies and let the dollars take care of themselves. The pottery pig seems to be the earliest animal in the savings bank menagerie. After that came the rabbit, the lamb, the watchful owl, the cunning fox , the avaricious eagle, the snatching monkey and the rest of the animal kingdom that either received our pennies through a slot or deposited them with astounding mechanical accuracy. Collectors are beginning to find this old-fashioned thrift an amusing field to explore.

In the past century the ingenuity of toy savings bank manufacturers reached its peak. Most of the banks were made of cast iron and realistically colored. The wonderful way in which the penny was finally deposited appealed to the child mind and so securely were these banks made that it taxed the cunning of parents to extract a cent. The style of figure usually reveals the decade in which it was made. These toys also gave birth to a moral code, for to rob a child’s bank is one of the lowest forms of thievery and to take out the money after once deposited was considered dangerous to youthful character.

While the architecture of house shaped banks was not all that might be desired, they were thoroughly efficient as banks. They were opened by a key — and the key was usually lost.

The avaricious male, both black and white, was a favorite form for toy savings banks. Some of these did tricks, too. Children were taught to give them pet names and thus shyly did they learn that "a penny saved is a penny earned."